WieWaldi Sam pointed out, this small 8 above or below the cfef sign is easy to overlook for old eyes

Not only for old ones. I've seen competent young readers with excellent eyesight get tripped up by these clefs.

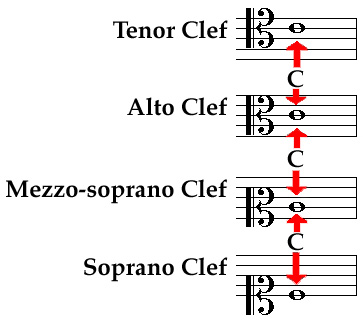

There are many cases where one of these clefs is implied, but a normal treble or bass clef is used. In a lot of choral music, the tenor part is written in treble clef, but everybody knows that it should sound an octave lower. Similarly, piccolo parts are written in treble clef, but sound an octave higher. And contrabass parts are usually written in bass clef, but sound an octave lower. Some editions use one of the clefs with the little 8 above or below, but many just don't bother.